by Jed Pressgrove

The Best Year in Gaming History or: Eating a Filet Mignon at McDonald’s

You might have read 2023 is one of the greatest years for video games or the best year of them all. You have maybe further noticed that the cited evidence for this claim involves a striking number of sequels* and remakes** — perhaps more sequels and remakes than you have ever seen acclaimed in a single year. Here’s an incomplete list of the sequels and remakes people often mention:

The Legend of Zelda: Tears of the Kingdom

Super Mario Bros. Wonder

Resident Evil 4

Super Mario RPG Remake

Baldur’s Gate III

Metroid Prime Remastered

Dead Space

Spider-Man 2

Alan Wake II

Final Fantasy XVI

Amnesia: The Bunker

Diablo IV

Star Wars: Jedi Survivor

God of War Ragnarok

Octopath Traveler II

Street Fighter 6

The Talos Principle 2

Pikmin 4

Armored Core VI: Fires of Rubicon

Assassin’s Creed Mirage

Mortal Kombat 1

System Shock

One might get the excitable impression that the greatest game of this greatest of years should be something that can be considered a sequel AND a remake. The obvious stance follows: Resident Evil 4 is the 2023 Game of the Year. Besides its coveted status as a sequel and remake, this GOTY candidate is appropriate for two other reasons:

1. The original Resident Evil 4, released in 2005 on the Nintendo GameCube, was widely considered the 2005 GOTY. It’s also one of the most influential games of the 21st century (quick top 5: Resident Evil 4, Dark Souls, Minecraft, PlayerUnknown’s Battleground, and Grand Theft Auto III).

2. The remake doesn’t change “too much” about the original but tweaks things that some people complained about (e.g., Leon, the hero, can move as he aims his gun; he stood in place while aiming in the original).

UNFORTUNATELY, I cannot deem Resident Evil 4 the GOTY of 2023 because playing it is the equivalent of eating a filet mignon at McDonald’s.

Imagine the scene: You’ve been driving for hours. You’re desperately hungry, you need to piss soon, and your tank is past half empty, so you take the next exit with a gas station. You notice the station has a McDonald’s. “Gee,” you say to yourself, “it’s been a long time since I’ve eaten Micky D’s.” You go inside, expecting to order something lame but edible like a Double Stack or Chicken McNuggets. Instead, you’re shocked to find a new promotion: the Filet McNon for $8. You slap yourself in disbelief. You know it’s an absolutely awful fucking idea, but you can’t help it. You order the Filet McNon and specify medium rare. You get the steak in about seven minutes. It looks like a filet mignon, but it doesn’t smell or feel or taste like one (it’s certainly not medium rare). But because you were ravenous, you inhale the Filet McNon and tell other people, “It’s good for fast food.”

This story sums up what the gaming world has done: exalting a game that resembles Resident Evil 4 but has been divorced of its humor (the remake’s self-seriousness is embarrassing), its original thrills (the introductory village battle now seems stilted), its rough edges (how about that quick-time-event fight with Krauser?), its bells and whistles (The Mercenaries is the greatest extra mode of all time), and the personal auteurist stamp of director Shinji Mikami. The Resident Evil 4 remake is a counterfeit product that disposes of creative authorship and threatens to rewrite history with its perfunctory doppelgänger of a title. Developer Capcom stopped caring about making good games years ago; the company is on the lookout for the most convenient moneymakers, fruit that hangs just inches above ground. The familiar is considered fresh.

*It’s not unusual for a proclaimed greatest year of video games — or any normal year — to feature numerous sequels. Three popular years are 1998, 2004, and 2017, all of which had their fair share of sequels. For those curious, here is my personal top 10 for each of those years:

1998

- Fallout 2

- Starcraft

- Final Fantasy Tactics

- Radiant Silvergun

- Metal Gear Solid

- Resident Evil 2

- Parasite Eve

- Tenchu: Stealth Assassins

- Metal Slug 2

- Mario Party

2004

- Metal Gear Solid III: Snake Eater

- Cave Story

- Paper Mario: The Thousand-Year Door

- Ninja Gaiden

- N

- Katamari Damacy

- Doom 3

- X-Men Legends

- Half-Life 2

- Alien Hominid

2017

- The Norwood Suite

- Nier: Automata

- Splasher

- Pyre

- West of Loathing

- Golf Story

- Mario+Rabbids: Kingdom Battle

- Fire Emblem Echoes: Shadows of Valentia

- Hellblade: Senua’s Sacrifice

- Steamworld Dig 2

**While remakes aren’t new in gaming, the demand for them has increased considerably in the last few years. People practically beg for game remakes on social media.

For the Love of Heaven, You’re Not SquareSoft

Playing Sea of Stars is like opening an ornate can of sardines — no beautiful packaging can elevate such a dull meal. The game’s presentation suggests Chrono Trigger on steroids. The graphics and sound effects are undeniably detailed, but all the audiovisual proficiency in the world means zilch when the vision amounts to easygoing nostalgia for the 1990s. This is no Iconoclasts, whose pixel art depicted the bizarre, provocative effects of supernatural creation. Sea of Stars is pretty in that predictable video-game-industry way: It wants you to cheer on the developers for their hard work behind the scenes.

At least Sea of Stars is visually competent. For all its pride about the 16-bit era, it forgets the adult melodrama in Final Fantasy IV and VI, the spirituality in Earthbound and Illusion of Gaia, and the constant plot twists of Chrono Trigger. The story in Sea of Stars has the dramatic intensity of a paddle-ball demonstration and the psychological insight of an episode of Barney & Friends. Any narrative that allows a character as foolish as Garl to flourish can’t be taken seriously.

The combat in Sea of Stars showcases the lowest form of inspiration. SNES RPGs introduced several notable tweaks to turn-based battles — ideas like Final Fantasy VI’s character-specific mechanics and Super Mario RPG’s timed button presses have profoundly impacted the genre. In recent history, Zeboyd Games and Terry Cavanagh have made turn-based fights more urgent and calculative with entries like Cosmic Star Heroine and Dicey Dungeons. Sabotage Studio, the team behind Sea of Stars, only musters an encyclopedic approach that echoes what has come before: combos, interruptions, and so on. The developer’s one noticeable wrinkle to tradition is a resource called Live Mana, which flies out of struck enemies and can be absorbed by your party members to boost their attacks — a reward system that attempts to conceal its mindlessness with flashiness. Even more disappointing is the paltry number of techniques for each character. No amount of daydreaming about the SNES days can rescue Sea of Stars from mediocrity.

The Gaming World’s Memory Continues to be That of a Hamster

Baldur’s Gate III has impressed me far more than Baldur’s Gate II, which has always been the blandest of revered RPGs. But the praise for it has been comical and ahistorical. Phrases like “unparalleled level of freedom” and “It’s everything you’ve ever loved about any roleplaying game, with +1 to all stats” imply nobody remembers the first two Fallout games, Planescape: Torment, or The Witcher II and III, not to mention classics like Earthbound and Chrono Cross. Back in 2019, many people acted like Disco Elysium was God’s long-delayed gift to RPG fans; four years later, Baldur’s Gate III seemingly erased Disco Elysium’s existence. Going by some reviews, one might think the game invented voice-acted dialogue during cutscenes!

A Zelda/Mario/Fire Emblem Realization

After subjecting myself to the clichés, contrived surprises, and clunky innovation of The Legend of Zelda: Tears of the Kingdom, Super Mario Bros. Wonder, and Fire Emblem Engage, I think we need a superhero who kills off media franchises. Or maybe a demon who corrupts them with modernism. The Legend of Zelda: A Link to the Online Divorce Court. Super Mario Liposuction and Fitness Journey. Fire Emblem: Polyamorous Pickleball.

Where will these franchises go next? More importantly, why care? These games have lost their elegance and exhausted their potential. You can’t even compare them to corporate property as limited as James Bond. At least the eternal spy movie phenomenon reflects something about politics, sexuality, and culture. I encourage all souls to stop feeling obligated to pay allegiance to neverending sagas. The less time we dedicate to the old, the more chances we have to discover greatness.

My Unranked Top Games of 2023

Mr. Platformer

Starts as an ode to Pitfall. Ends as a troubling avant-garde revelation about the hollowness of completionism. Super Mario Bros. Wonder wishes it had as many compelling jumps. Terry Cavanagh is the best auteur in video games.

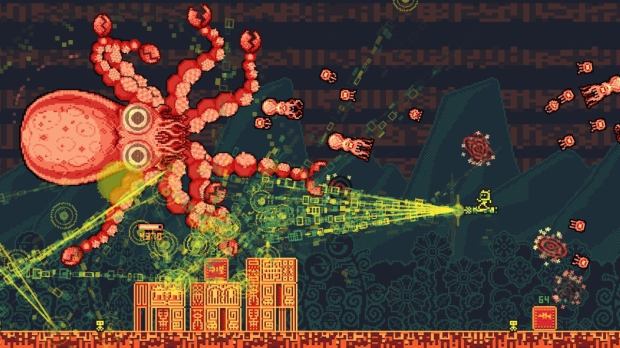

Boneraiser Minions

Another Vampire Survivors follower, only this time the imitator surpasses the popular landmark (and with no sleazy overlong allusions to casino games every time you open a damn treasure chest). Whereas Vampire Survivors featured a fairly predictable leveling system, Boneraiser Minions encourages mad-scientist ingenuity with its intimidating slew of crossbred demonic helpers, bizarre relics, and environmental traps and bonuses. This is what playing as the Necromancer in Diablo II should have been like. And yes, Boneraiser Minions has enough juvenile sex puns to make one wonder whether the developer is in junior high school.

Baldur’s Gate III

Baldur’s Gate III rejects its predecessor’s biggest weakness: those real-time skirmishes in which dull-looking avatars awkwardly swing their weapons at one another until someone perishes. The turn-based contests in Baldur’s Gate III marry the high-stakes drama of an XCOM firefight with the kookiness of an experimental puzzler. And while the writing can be quite goofy — I despise the Telltale-Games-esque messages about whether your party members approve of your decisions — the outlandish scenarios are charmingly depicted.

Gravity Circuit

Mega Man remade into a cathartic beat-em-up. The whole point is the style with which you pummel the nuts, bolts, and other components out of irritating robotic forces. The Capcom fanboys who complained about my damning Mega Man 11 review should expose themselves to the precarious levels and chained attacks of Gravity Circuit. The only thing that dampens the action is superfluous character dialogue.

Pseudoregalia

“Game feel” is one of those tortured gaming phrases that can haunt anyone who has a smidgen of dignity. Pseudoregalia nonetheless brought the term to mind because no 3D platformer has ever felt this precise and dynamic. I would rather play Pseudoregalia than any of the Nintendo 64 and Playstation 1 games that inspired developer rittzler.

Void Stranger

A sense of ominous nihilism hangs over this enigma. Not since Solomon’s Key have single-screen quests aroused so much curiosity about secrets that may or may not exist. Once you become accustomed to the puzzles, you find a tree that offers the option of rest. Resting literally closes the game. When you return to Void Stranger (perhaps bringing the vestiges of your own dreams into the game world), you see visions of a time when the protagonist isn’t trapped in stacked basements. But the nightmare again surfaces and the puzzles shift and any confidence you may have had about grasping the meaning of it all vaporizes. A part of me doesn’t want to peel back the layers of Void Stranger. The mysteries are enough.

Pizza Tower

This is psychologically unstable art drenched in pop smarts. What if the speed of Sonic the Hedgehog was a sign of excruciating anxiety? What if the transformations of Super Mario Bros. were feverish and awkward instead of empowering? Pizza Tower exposes the feigned emotions of big-budget games as dog treats for stressed-out populations. It acknowledges the insanity of life and gaming. I get nervous looking at it.